Where Elizabeth Found Whitman

December 7th, 2009 § 0 comments § permalink

“Years of the Modern” by Walt Whitman

Years of the modern! years of the unperform’d!

Your horizon rises, I see it parting away for more august dramas,

Visitors Center Script: Whitman and the Beats

December 3rd, 2009 § 2 comments § permalink

Whitman and the Beats

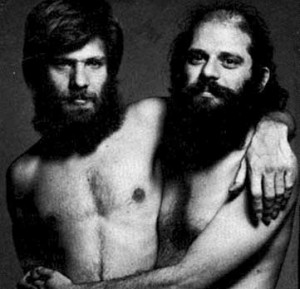

Peter Orlowsky and Allen Ginsberg

The Beat Generation–poets of the 1950-60’s who rejected mainstream American culture in favor of poetic and spiritual libration. The Beat poets experimented with drugs and alternative forms of sexuality, and developed an interest in Eastern thought and spirituality. Among their most famous works: Howl by Allen Ginsberg, On the Road by Jack Kerouac and William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch.

Jack Kerouac was a proponent of stream-of-consciousness writing, a style that Ginsberg later adopted. This can be compared to Whitman’s Specimen Days and his in-the-moment “unedited” prose of detailing Civil War events from the capitol.

Ginsberg also uses long-lines in an approach to capture the rhythm of jazz with the length of a breath–Howl and other poetry is particularly well-suited to oral recitation:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat

up smoking in the supernatural darkness of

cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities

contemplating jazz…

Howl by Allen Ginsberg

Whitman was among the first to popularize long lines of verse, which the Beats readily adopted for its poetic power and oracular quality.

Whitman and the Beats are similar in more than just style–they share many poetic themes and political beliefs.

One of these is a distaste for American materialism. The Beats struck down mainstream culture for its materialism, embracing spontaneity and liberation over conventionality. Whitman also criticized materialist culture, stressing an appreciation of the simpler things in life, among them, the beauty of nature and the human body.

The Beats also shared Whitman’s fascination with the sexualized male form. Although Whitman never admitted to homosexuality, Ginsberg felt no shame with his own sexual relations with Peter Orlowsky, his life-long partner.

Whitman and the Beats were both poets that were involved with the change of the nation’s character in the face of war. Whitman still retained a somewhat positive outlook on America throughout the Civil War, even after all the casualties that he witnessed in the hospitals. Ginsberg and the Beat poets adopted a far more grim approach, writing about the alienation of men and women and the destruction of individuals of great character by malign societal control and conformity.

Nevertheless, both poets awoke America with their radical poetry and politics and shaped the cultural, political and literary scene for decades to come.

Jack Kerouac at a reading

Christine’s blog, Whitman and the Equality of Women

Jessica’s blog, Whitman, Bucke and Carpenter

Whitman’s Late Poetry

November 19th, 2009 § 2 comments § permalink

The last two weeks of class discussion have made me think long and hard about the changing nature of Whitman’s poetry in his later years. The famous poems that are highlighted in poetry courses include a broad selection of his early works, but very few seem to mention his later verse. I had no idea about Whitman’s years in Camden until I came to this university. And while his late poetry does not have the martial rhyme or political punch of his early writing, the quiet contemplation and appreciation of nature and life is touching.

If Whitman ever had fears about dying, it does not show in his poetry. Even with his debilitating ailments, he only writes about the appreciation of life, never about his struggles with sickness or the fight from day to day. The diminishment of energy is evident in these later works; many of his poems consist only of a few lines, where earlier Whitman could have expanded them into grand poems with scores of lines.

The metaphors that Whitman uses are also far more commonplace. Old age is the night of a long day, or the winter of the seasons of life. His poetry, once full of direct detail and on-the-scene footage now resorts to imagery, metaphor and symbolism in order to catch its effect. It is no surprise that Whitman has turned introspective–the forces he is dealing with now, most of all death, are intangible and largely unknown.

Cinepoetry

November 15th, 2009 § 1 comment § permalink

All goes well! I’ve spent somewhere around 10 hours filming and editing my cinepoem. It’s a little short–3:15, but quality work, I assure you. The clips are cut and synched with music. Believe me, audio editing takes forever. It’s a good thing I’m not new to video editing and the like.

The real question is whether to simply use subtitles, or use a voiceover, or both. I despise hearing my own voice, but I know someone who could do well speaking the lines for me, but I’m still unsure. Just subtitles would let my nicely timed music take a bigger role–and somehow it’s more artsy that way.

Here is an interesting use of voiceover and subtitles–that is, the use of creative typography instead of images. The poem is Kipling’s “If”:

XX

Elizabeth for Nov. 12th

November 10th, 2009 § 1 comment § permalink

Whitman’s writing from Sands and Seventy centers itself on reflections on the past as well as meditations on the nature of death. The poems in this selection are far shorter than the grand verse of Whitman’s youth, not to mention the first publication of his grand epic Leaves of Grass. The tone is markedly humble, but little hints and flashes of the strong rhetoric of his Drum-Taps days appear here and there throughout his poetry.

“Election Day, November, 1884” is one of these. Whitman praises America’s democratic process, a force that excels even the greatest natural wonders of the nation. This election is termed “a swordless conflict,” even though the face-off between Grover Cleaveland (D) and James G. Blaine (R) was known for vicious mudslinging and personal attacks on morals and integrity. As we all know from history, Grover Cleaveland won the election, becoming the first democratic president elected since before the Civil War. While learning about the presidents as a child, I could never forget that Cleaveland was the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms in office: 1885-9 and 1893-7.

Whitman also offers up a common poetic metaphor for his thoughts on death. The Sea has always been a popular source of poetic symbolism, representing many things, including birth and rebirth, death, and mysterious femininity. Whitman draws on the masculine strength of death as a source of poetic inspiration itself, imagining that the waves have their own voices: “many a muffled confession–many a sub and whisper’d word,/As of speakers far or hid” (Fancies at Navesink, 27-8).

These wave-poets also suffer from debilitating old age, just as the many poets of ancient times: “Poets unnamed–artists greatest of any, with cheris’d lost designs,/Love’s unresponse–a chorus of age’s complaints–hope’s last words,/Some suicide’s despairing cry, Away to the boundless waste, and never again return” (30-33). Whitman embraces the idea of oblivion of death, avoiding typical flowery language and purple prose associated with passing.

Whitman’s poetry is subdued, yet not defeatist. While the poet may be unsure about his legacy, he shows no fear in the face of death in his poetry, but rather looks forward to nature’s cleansing of the debilitating pains of old age. The memories of his past are precious to his time in old age, and his reflections are just as essential to his poetry and prose as are his war poems and nationalistic verse.

Elizabeth for 11/5

November 5th, 2009 § 2 comments § permalink

Songs of Parting and Whitman’s poetry from later years is particularly poignant in its acceptance of the oncoming specter of death. It seems that the atrocities of the Civil War made the poet all too familiar with scenes of passing, and his poetry is calm and accepting of death’s shadow. Whitman is sure of his survival through his works of poetry and prose, but the mentions of his fading health are touching and deeply saddening.

I shall go forth,

I shall traverse the States awhile, but I cannot tell wither or how long,

Perhaps soon some day or night while I am singing my voice will suddenly cease.

(As the Time Draws Nigh, 3-5)

Whitman realizes that he soon may not be able to continue writing poetry, that his weak health may prevent him from continuing his work as America’s poet. But he continues to press on, looking ahead to the future of an America that wholly embraces equality. Whitman looks forward to an America that realizes the civil rights of citizens of all races. He stands against the divisions of caste and the classical hierarchy of European monarchical rule. Through technology, such as the steamship, the telegraph and the newspaper, Whitman looks forward to a global, integrated world, much like our modern world today.

It is interesting to think of Whitman’s embrace of technology and the great push in advancements that have happened in the last twenty years, not to mention the last century. Today’s world is dependent on global communication, trade and business, and political negotiation. We cook international foods in our own kitchens, we instantly chat with men and women from around the globe. The internet is a force that spreads democracies in autocratic nations in a way that war and troops never could. Our cultural borders are constantly expanding and while the world grows smaller, our own lives grow richer because of it.

It is hard to imagine what poetry Whitman would pen in response to this globalization, but I am sure that he would be in the forefront of it all, bringing us into awareness of the changes in America occurring around us.

Would Whitman be one of the men walking down the streets of Philadelphia with his blackberry? Even so, I am sure he would be among the few of us to put his phone away to take a real look around.

Elizabeth’s Material Culture Museum Exhibit

October 20th, 2009 § 1 comment § permalink

The Tomb of Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman’s final resting place is located in Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey. The cemetery opened in 1885, only seven years before Whitman’s death, making it one of the oldest cemeteries in New Jersey. The cemetery covers over 130 acres of land, full of trees, sloping hills and gardens (Wikipedia).

In 1890, Whitman began making preparations for the spot of his burial, signing a contract for $4000 for the construction of a “burial house” in the cemetery, sturdy and geometric, carved roughly of granite with his name emblazoned on the front stone face. But what moved Whitman, usually the model of frugality, to decide on such an expensive burial structure?

Although Whitman grew up in poverty, by the last fifteen years of his life in Camden his salary averaged $1200 a year, a third more than the standard salary of an American worker (Reynolds, p. 32). By that standard, the cost of the tomb was over three times his annual salary. But Whitman cleverly relied on his good connections to pull him through the transaction–after paying the first $1500, he refused to pay for the last installment, relying on a rich friend to pick up the rest of the tab. Yet Whitman was quite liberal with the rest of his estate and possessions, giving liberally to his family members, five of which occupy the tomb along with him.

Young Harleigh Cemetery

One question that arises regards Whitman’s choice of such a young graveyard in which to build his tomb. Practical concerns such as space for the large stone structure were certainly concerns, and Whitman undeniably had the choicest pickings of the site for his location. But there seems to be evidence that Whitman may have been given a good deal by Harleigh Cemetery. According to one source, the cemetery convinced Whitman to pick a plot in order to increase business. By burying Whitman, a famous poet as well as a Camden local, Harleigh Cemetery rose in value and in business dramatically (Tomb of Walt Whitman Camden NJ).

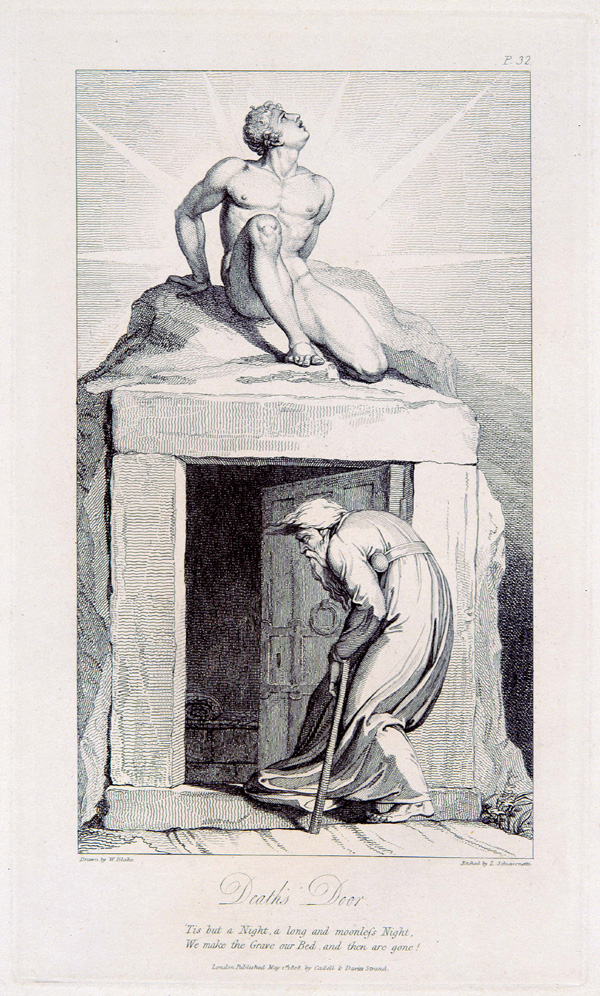

Blake’s “Death’s Door”

The model for Whitman’s tomb is based on William Blake’s engraving, “Death’s Door” which Whitman discovered in 1881 (Ferguson-Wagstaffe). Whitman submitted a sketch to his literary executor, with the comment, “Walt Whitman’s Burial Vault–on a sloping wooded hill–grey granite–unornamental–surrounding trees, turf, sky, a hill everything crude and natural.” Whitman’s concept of a tomb was one carved out of nature, part of the earth yet separate from it. It is clear that Whitman intended to make a statement, but he disliked the grand, European style of mausoleums. The result is of Whitman’s desires was a tomb built to be earthen and sturdy, rather than polished and refined.

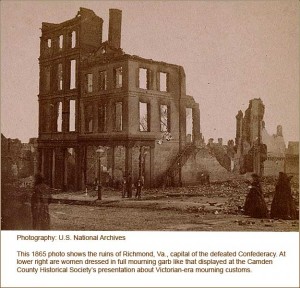

Burial Rituals

Rituals regarding burial began to change in the nineteenth century, leading to new practices and a new design of graveyard. The Civil War was one of the catalysts, quickly robbing many households of fathers and sons–totaling up to approximately 600,000 casualties (Historic Camden County). Isolated burial grounds soon gave way to cemeteries that took the form of pubic parks. Victorian garden landscapes became the standard, where relatives would come to pray for, and picnic with, the deceased. Harleigh Cemetery represents one of these, founded after the civil war. Whitman’s request for a tomb was not unusual during this period of public graveyard revival.

Rituals regarding burial began to change in the nineteenth century, leading to new practices and a new design of graveyard. The Civil War was one of the catalysts, quickly robbing many households of fathers and sons–totaling up to approximately 600,000 casualties (Historic Camden County). Isolated burial grounds soon gave way to cemeteries that took the form of pubic parks. Victorian garden landscapes became the standard, where relatives would come to pray for, and picnic with, the deceased. Harleigh Cemetery represents one of these, founded after the civil war. Whitman’s request for a tomb was not unusual during this period of public graveyard revival.

Today Whitman’s tomb remains a site for the public, both of his literary fans and of roaming tourists. The tomb remains unchanged on a grassy hillside in Harleigh cemetery, open to visitors.

In Autumn Rivulets, Whitman’s Outlines for a Tomb ends with a passage of the narrator transcending the borders of America and beyond.

O thou within this tomb,

From thee such scenes, thou stintless, lavish giver,

Tallying the gifts of earth, large as the earth,

Thy name an earth, with mountains, fields and tides.

Nor by your streams alone, you rivers,

By you, your banks Connecticut,

By you and all your teeming life, old Thames,

By you Potomac laving the ground Washington trod, by you Patapsco,

You Hudson, you endless Mississippi–nor you alone,

But to the high seas launch, my thought, his memory.”

Instead of being weighed down by death, the narrator transcends borders with his thoughts. In this way, Whitman transcends his own death, not only through the erection of his tomb, but through the survival of his poetry and prose and those who study and learn by his works.

Works Cited

Fergusun-Wagstaffe, Sarah. “‘Points of Contact’: Blake and Whitman–Sullen Fires Across the Atlantic: Essays in Transatlantic Romanticism.” Harvard University. Romantic Circles. University of Maryland.

“Harleigh Cemetery, Camden.” <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harleigh_Cemetery,_Camden> Wikipedia.

Levins, Hoag. “Civil War-Era Death and Mourning Customs and Rituals” HistoricCamdenCounty.com. October 28th, 2002. <http://historiccamdencounty.com/ccnews43.shtml>

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman: Benjamin Franklin’s Representative Man. Modern Language Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Spring, 1998), p. 29-39.

“Tomb of Walt Whitman, Camden NJ, American Guide Series on Waymarking.com” Waymarking.com. <http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM70J8_Tomb_of_Walt_Whitman_Camden_NJ>

Whitman’s Brain

October 20th, 2009 § 0 comments § permalink

All of us are familiar with Whitman’s fascination with physiognomy, the assessment of a person’s character by their outward appearance. From what I’ve heard, he had his own head read on several occasions.

It makes sense, then, that Whitman donated his own brain to science upon his death. His brain was kept preserved at the Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, as part of a collection of other brains from intelligent and renowned figures.

Unfortunately, at some point in time Whitman’s brain was dropped by a lab assistant–and therefore ruined and discarded.

Poor Whit–he must have turned over in his grave.

For the curious, here is the article where I found this.

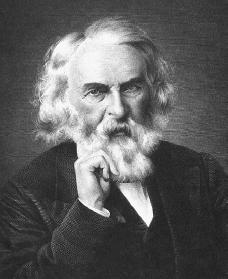

Elizabeth for Oct 22nd: Death of Longfellow

October 20th, 2009 § 0 comments § permalink

“For want of anything better, let me lightly twine a spring of the sweet ground-ivy trailing so plentifully through the dead leaves at my feet…and lay it as my contribution on the dead bard’s grave” (941).

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

In Specimen Days on April 3rd, 1882, Whitman learns about the death of Longfellow through the newspaper and reminisces on the accomplishments of the fellow poet. His comments seem to weigh disapproval with plentiful praise, beginning with, “Longfellow in his voluminous works seems to me not only to be eminent in the style and forms of poetical expression that mark the present age, (an idiosyncrasy, almost a sickness, of verbal melody,) but to bring what is always dearest as poetry to the general human heart and taste” (941.) Whitman is not a fan of Longfellow’s insistent use of rhyme, the usage of which is not mere style, but a sickness, a dependance on formal verse. Poetry that reads like a song is suited to the common man’s taste, but this appears to be a degradation rather than an enhancement of the form. Longfellow adapts poetry to be readable by a large audience, simplifying it and its art for the general populace.

Yet Whitman goes on to claim that Longfellow represents “the sort of bard and counteractant most needed for our materialistic, self-assertive, money-worshipping Ango-Saxon races, and especially for the present age in America–an age tyrannically regulated with reference to the manufacturer, the merchant, the financier, the politician and the day workman–for whom and among whom he comes as the poet of melody, courtesy, deference” (942). Longfellow is the one poet to take the gift of poetry beyond the literary minded and share its music and its power with the everyday workman. In this way, Longfellow democracizes poetry, making it accessible to all those who are able to read. Poetry now has its place beside storytelling and biblical texts as one of America’s most popular literary pastimes.

Longfellow is the “universal poet of women and young people”–a poet of sentimentality (942). Whitman defends Longfellow from his critics who claim that the poet’s lack of originality. Originality is dependent on the exploration and study of the literary figures and works of the past. Before America, the New World, “can be worthily original, and announce herself and her own heroes, she must be well saturated with the originality of others, and respectfully consider the heroes that lived before Agamemnon” (943).